Paid participation and governance: Stipends for Tukano advisors and performers, translators, apprentice artists, plus a community advisory group with approval rights on story, aesthetics, and language.

Skills and access: Ongoing workshops and paid apprenticeships in Vaupés, with curricula co-designed by elders and youth, enabling community members to contribute to the project while creating new opportunities and practical know-how to use technology as a tool for cultural preservation.

Equipment & tooling: A minimum hardware bundle donated to the community so they can record, scan, and capture locally.

Language & music preservation: Professional recording of Tukano speech, songs, dances, and instruments, archived with community access and permissions.

Cultural asset in digital form: Delivery of a 3D library od assets reconstructed and scanned, archived with community access and permissions.

Transparency: A published benefit-design plan, quarterly check-ins, and simple public reports on money spent for community benefits.

Collaborating with the Tukano

Co-authorship, Adaptation, and Community-Defined Benefits

For the past seven years, we’ve worked in Piracuara, Vaupés, alongside the Guerrero family, custodians of Yu’upuri Wa’uro’s story, transcribing sacred narratives and building a deep relationship of trust. The narrative belongs to the Tukano. We adapted one of their sacred stories into a structure that works as a video game for a global audience, then returned with a full script for community review. Elders and representatives corrected inaccuracies, refined culturally incongruent elements, and aligned locations, rituals, and cosmology. This iterative process will continue through production, so the game remains both culturally accurate and genuinely engaging for broad audiences. Our goal is to share this story widely, strengthening how the Tukano see themselves, and how the world sees them.

Community-Defined Benefits

Historically, private initiatives arrived with pre-packaged “solutions,” often missing real day-to-day needs. We’re flipping that model: we listen first, and co-define benefits with the Tukano through patient, recurring workshops. We work from a benefit-design plan (not a fixed prescription), giving the Tukano time to reflect and set priorities at their own pace. However, there are some baseline benefits, we’ve ring-fenced that will happen regardless of the project’s financial outcome.

Baseline commitments

Paid participation and governance: Stipends for Tukano advisors and performers, translators, apprentice artists, plus a community advisory group with approval rights on story, aesthetics, and language.

Skills and access: Ongoing workshops and paid apprenticeships in Vaupés, with curricula co-designed by elders and youth, enabling community members to contribute to the project while creating new opportunities and practical know-how to use technology as a tool for cultural preservation.

Equipment & tooling: A minimum hardware bundle donated to the community so they can record, scan, and capture locally.

Language & music preservation: Professional recording of Tukano speech, songs, dances, and instruments, archived with community access and permissions.

Cultural asset in digital form: Delivery of a 3D library od assets reconstructed and scanned, archived with community access and permissions.

Transparency: A published benefit-design plan, quarterly check-ins, and simple public reports on money spent for community benefits.

The game as an excuse of preservation

Wa’uro isn’t just a story you play, it’s a framework to safeguard one. We’re using cutting-edge production tools and community-led processes to help the Tukano record voices, gestures, and material culture in ways that can be shared, taught, and lived again.

Actors of their Own Story

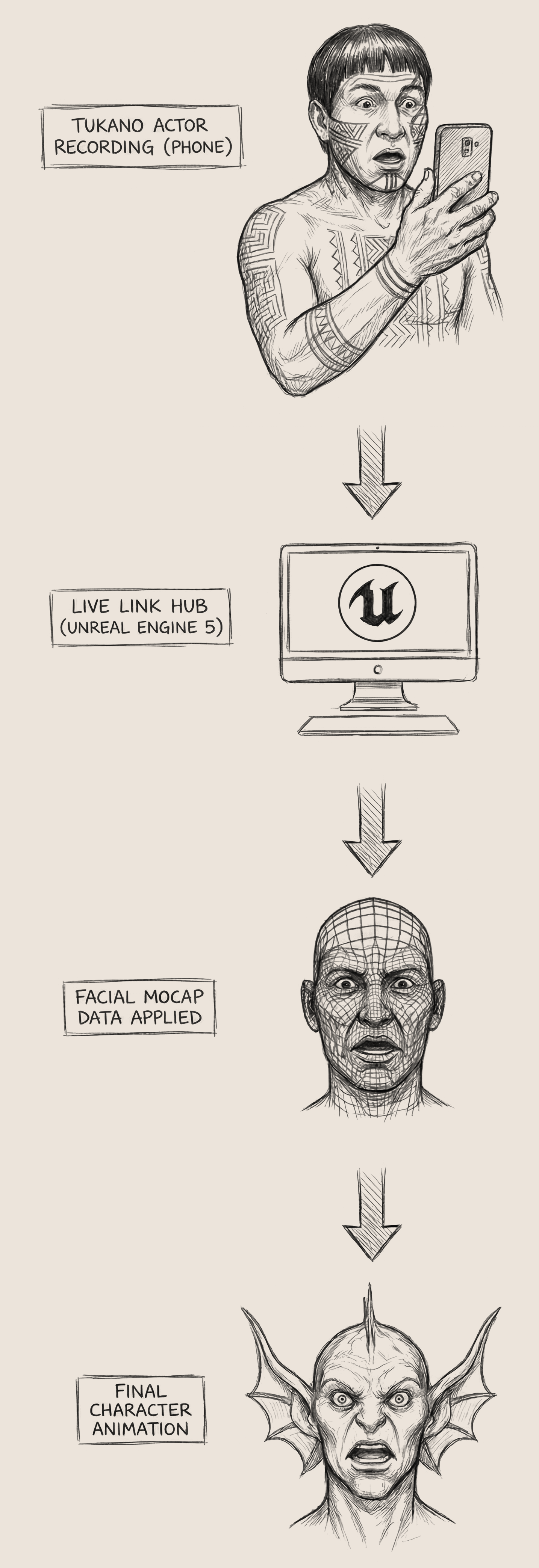

Using cutting-edge, machine-learning-assisted facial motion capture, we record high-quality performance from simple cellphone video in the field, so Tukano community actors can voice and embody their own ancestors in their own language. In the past, this was prohibitively expensive or logistically impossible, but this pipeline lets us capture Tukano performances, iterate remotely, and reshoot with minimal friction, even when the community lacks high-end gear or we aren’t in the same location. It also makes Tukano the primary in-game language and turns collaboration into true co-performance. We train local performers on the capture workflow, then drive MetaHuman animation directly, bringing authentic voices, expressions, and cultural nuance into every scene.

A Time-Proof Museum

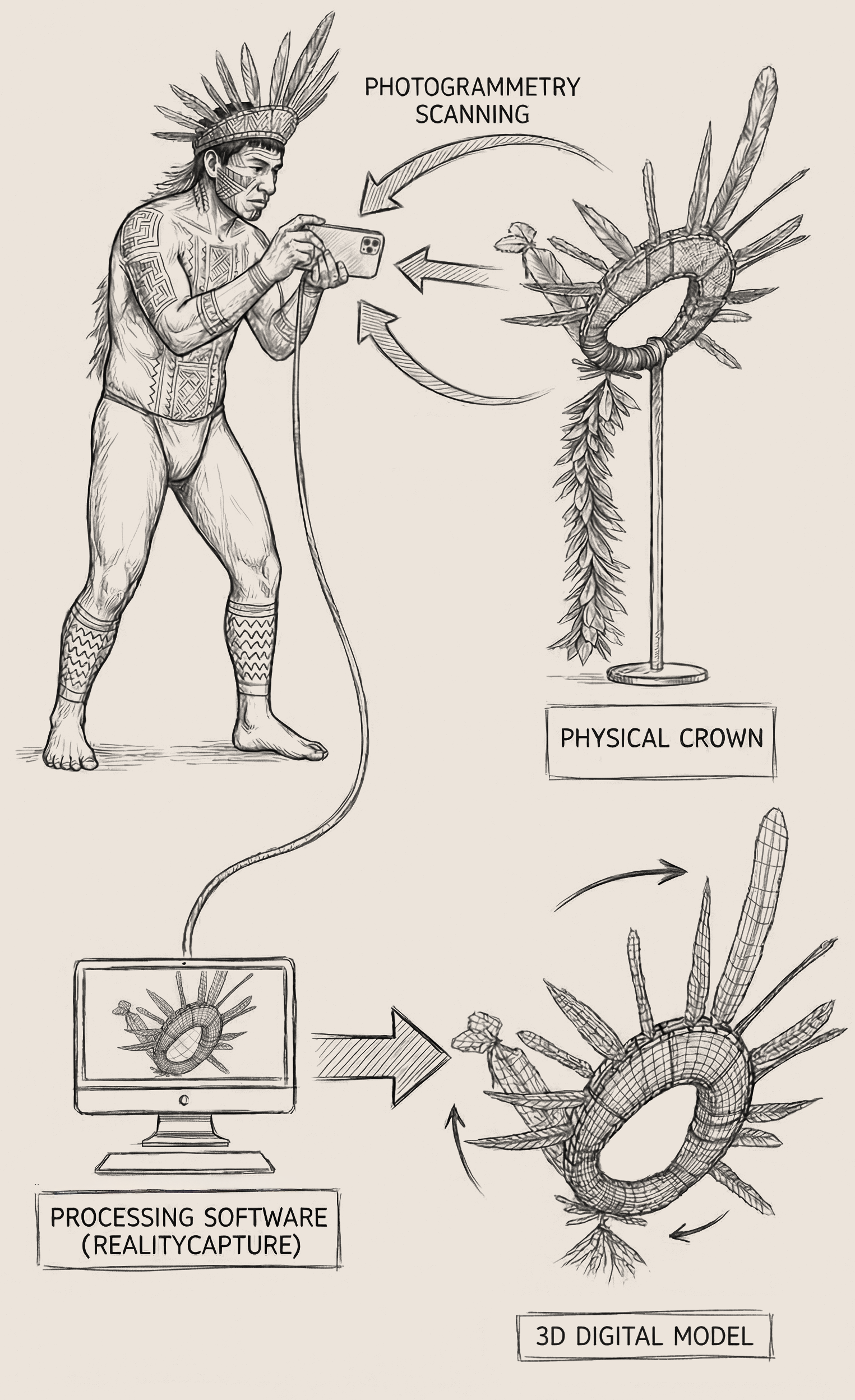

We are building a living 3D asset library that safeguards Tukano material culture for the long term. When objects still exist, we capture them with photogrammetry, shooting many overlapping photos to reconstruct accurate, Unreal-ready models. When objects have vanished, we rebuild them from nineteenth-century expedition notebooks, drawings, and photographs, then refine each piece with Tukano guidance. The result is a faithful, growing archive that preserves form, story, and use for future generations and the game.

How photogrammetry works

We take many overlapping photos of an object under even lighting, from all angles. Software finds common points between images and builds a precise 3D mesh. We then clean the model, create efficient geometry and UVs, and bake high-quality textures so it’s ready for games, film, and education.

Reconstructing what no longer exists

For lost objects, we combine historical sources, expedition notebooks, museum catalogs, engravings, early photographs, with interviews and review sessions with Tukano elders. We prototype variations, validate proportions and materials with the community, and converge on a culturally faithful digital twin

Why it matters

The 3D library lives at the heart of Wa’uro. In game, these UE-ready artifacts populate levels, props, and interactive quests, turning objects into mechanics that teach function, symbolism, and proper contexts of use. In community, the same models become a hands-on learning kit for Tukano youth through workshops and school sessions, where they explore, name, and even help author assets, building skills in scanning, modeling, and cultural documentation. Because many items no longer exist locally, many young people have never seen them, so beyond teaching digitization the library also reintroduces each object’s name, use, and meaning into community memory. In academia, each asset ships with metadata, sources, and community notes, enabling research, classroom use, and comparative studies across time and regions. One library, three purposes, a single ethic of care, where every object serves play, education, and conservation at once.